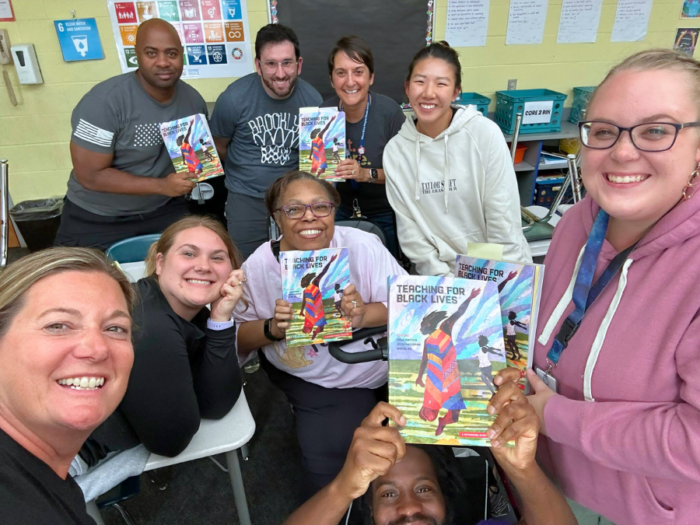

Jan Mitchell, 6th-grade assistant principal at Dillard Drive Magnet Middle School (6–8), and Charlesa Peoples, 8th-grade assistant principal at West Cary Middle School (6–9), are co-leading a Teaching for Black Lives study group with 24 educators in Raleigh, North Carolina. Peoples said, “We want to build on what we have already started by continuing to create safe spaces, teach students and staff how to be allies and co-conspirators, affirm our Black and Brown students, analyze our response to discipline in an effort to close the disproportionate gaps as it relates to suspensions, and focus on more restorative practices.”

In November, the study group welcomed Jesse Hagopian, Teaching for Black Lives co-editor, and Julia Salcedo, Teaching for Black Lives study group coordinator, to their bi-monthly meeting via Zoom. Their smiles embraced us when we entered the room. Mitchell and Peoples led book studies together in the past and their appreciation for each other was heartwarming as they introduced themselves.

After quick introductions, members spent the first few minutes journaling in response to the prompt from the facilitation guide:

How has participating in a Teaching for Black Lives study group impacted your year so far? Are you noticing any changes in yourself? Your practice? Your awareness?

Mitchell invited members to share what they wrote with the rest of the group. Lexi Chadwick, 7th-grade special education teacher, said,

It’s given me the opportunity to hear others’ struggles and intentionally learn how to become a better teacher, ally, and activist because of it. Having these conversations allows me to address my own prejudices and experiences while also learning how to empathize with my students.

Peoples said,

The Teaching for Black Lives study group has caused me to pause and reflect on some of my practices as an administrator and contemplate: If I had to give a student a consequence or a suspension, what could have been done differently leading up to the situation? What can I or we do differently as a school, should the instance come up again?

Christopher McCormick, business and computer science teacher, said,

I’ve become more aware of my surroundings and I do understand my role as a Black male teacher. When I interact with all students, I am being my best possible self and constantly reflecting and addressing my biases.

For the remainder of the meeting, members split into breakout groups to discuss one of the three assigned chapters they read and then regrouped to share-out key takeaways.

Members who read “Teaching SNCC: The Organization at the Head of the Civil Rights Revolution” by Adam Sanchez, appreciated “the emphasis on young people as a part of the Civil Rights Movement” and agreed on the importance of “empowering students’ voices and knowing that students have power to enact change.”

Allison DuVal, family and consumer sciences teacher, highlighted the line: “Probably the most important part of SNCC’s legacy is not its nonviolent direct action tactics but its base-building through community organizing.”

Hagopian shared his experience teaching this lesson with his students. He said,

It will bring your classroom to life! Students debate whether Martin Luther King should be invited to their March. That was what students did back then. He wasn’t this God icon that we have now, he was an activist and an organizer who had a strategy and the students had another strategy. When kids really wrestle with the real questions of the Black Freedom Movement they see these people as three-dimensional and they see themselves. ‘If those young people change the world then maybe we can too.’

Participants expressed their appreciation for Hagopian’s example and felt supported to implement these lessons in their classrooms.

Kamilla Wright, 6th-grade math teacher, underscored the importance of these conversations with students and said,

It seems like a long time ago to our students but it really isn’t. As educators, we need to keep that in the forefront, that what we’re talking about isn’t really that far removed and if we don’t learn from our history, we will be right back in some of those positions but in a different way.

Educators in Teaching for Black Lives study groups are leading the change in classrooms around the country to give students the tools and space to speak their truth and rebuild a community of support. Our hope is continuously renewed as we hear from teachers who are committed to making our schools sites of resistance, justice, joy, and liberation.